I would like to collect information and advice on a problem I call “solving for the invisible.” Visual clues in all forms of communication cause this problem, which visually impaired people often face in a group.

In addition to sharing my personal experience, I want to propose an AI-based solution using Large Language Models.

How language makes it invisible

The most common instances of this problem can be attributed to the use of pronouns. To warm up, let’s notice the use of the word “it” in the following two sentences.

· I could not put the gift in the box. It was too big.

· I could not put the gift in the box. It was too small.

Most children aged 4 years (and ChatGPT*) can decipher the noun referred to by “it” in the two sentences above. It is indeed a matter of paying attention to the context.

Children can also follow the use of the word “it” when it involves visually pointing at something, as in “go get it”

Now, most people are sensible enough not to point at things and say to a blind woman, “Go get it.” At least they won’t behave like this while dealing with her personally. But as part of a group say in a meeting or a classroom, this natural tendency to point at things poses some interesting challenges. The challenge is to identify what remains invisible to the language, and I would refer to it as “solving for the invisible”. Let’s see two examples:

Visual presentation for groups

Consider a scenario in a classroom where information is presented visually on a screen or a blackboard, and a person possibly visually impaired (who also might not want to interrupt the teacher every other second) cannot see it.

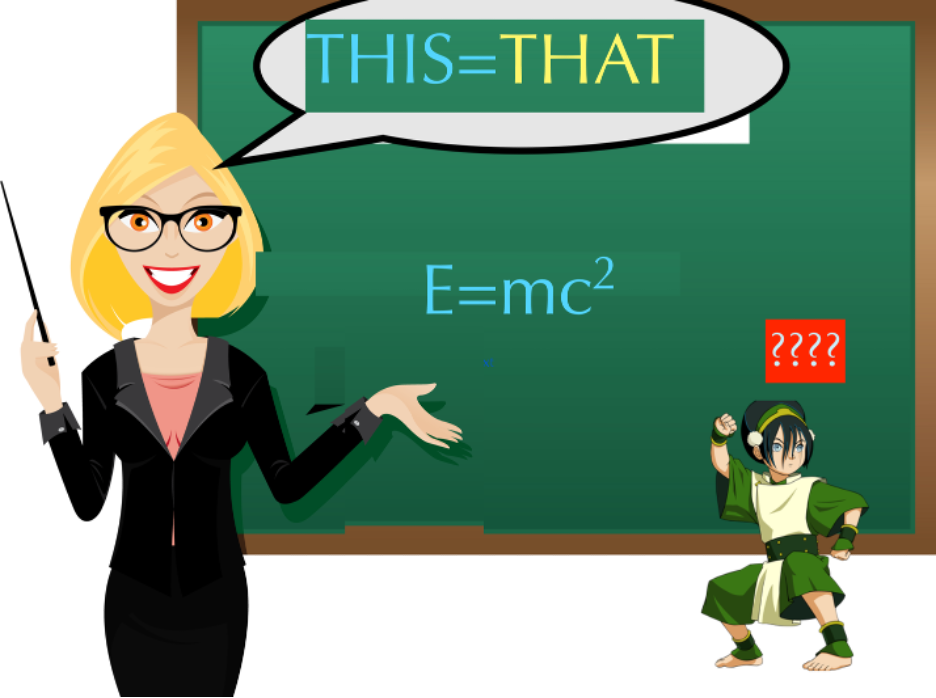

Now, our physics teacher is generous, kind, and an excellent communicator and knows when to use visual images. But she tends to say “This is equal to that,” by pointing out to the expressions on the board

As presentations with pictures have become more common, pronouns have replaced what earlier used to be “a thousand words.” A typical math lecturer often points to the board and says, “This here is equal to that there,” whereupon she points to the “this” and “that” for everyone to see.

Eavesdropping

Imagine that you have managed to bug your enemy’s military headquarters with some microphones, which provide an audio stream of all conversations. However, in the absence of video information, the listeners have to guess what maps or documents are being considered, not to mention all the code words being used.

This is the same problem:-)

Just a nod

Although I have been calling out the pronouns, they are at least solvable. The worst thing in communication happens when people use no language, merely using a gesture, smile, or nod.

I ask my daughter, “Do you want more soup?” She nods, and I ALWAYS KNOW the answer.

Soundless communication is beyond the scope of this article, maybe we can talk about it another time.

Solution: Attention is all one needs

A challenging part of being a visually handicapped person is that you have to guess what is being pointed at without actually being able to see.

This is how the processes work out in most cases when the presentation is smooth and sufficiently long.

As you pay attention to the speaker in a lecture, you naturally keep track of what is essential. As an automatic background process, our brain gets primed to recall or jump to many associated ideas. This allows us to guess some of the pronouns immediately without having to ask. However, it can get a bit complicated.

Sometimes, either the guess is wrong, or no obvious candidate comes to mind. With time, with a few misses, you end up with a small jigsaw puzzle or a crossword. You do have a fair bit of information available, but there are still many confusing or missing details.

At this point, you can just ask politely to read out the visual information. Or, you choose to play your own little game. Build your own mental picture of the presented subject with attention to what you know, what is important (the question being discussed, for example) and the marked unknown bits. The unknown bits are what you did not see as it was visually presented.

If you manage to pay attention, some representation of the neurons tends to fire, and you can feel tingling when you get it right. You can fill in the blanks! Otherwise, you hope that at least one of your friends took good notes.

Just as an encouragement, the legendary mathematician Henri Poincare was also shortsighted and could not read blackboards. He seemed to have also solved the problem of solving for the invisible. But unfortunately, I cannot ask him how he did that. If you have a suggestion, please do write a comment.

In the meantime, I want to explore some AI-based solutions.

1. Phone/Camera device with OCR and text-to-speech. Many apps can read text using cell phone cameras. But there are two drawbacks. First, you need to know where to point the camera. Second, such speech-to-text apps still do a poor job of reading formulas and maps/charts.

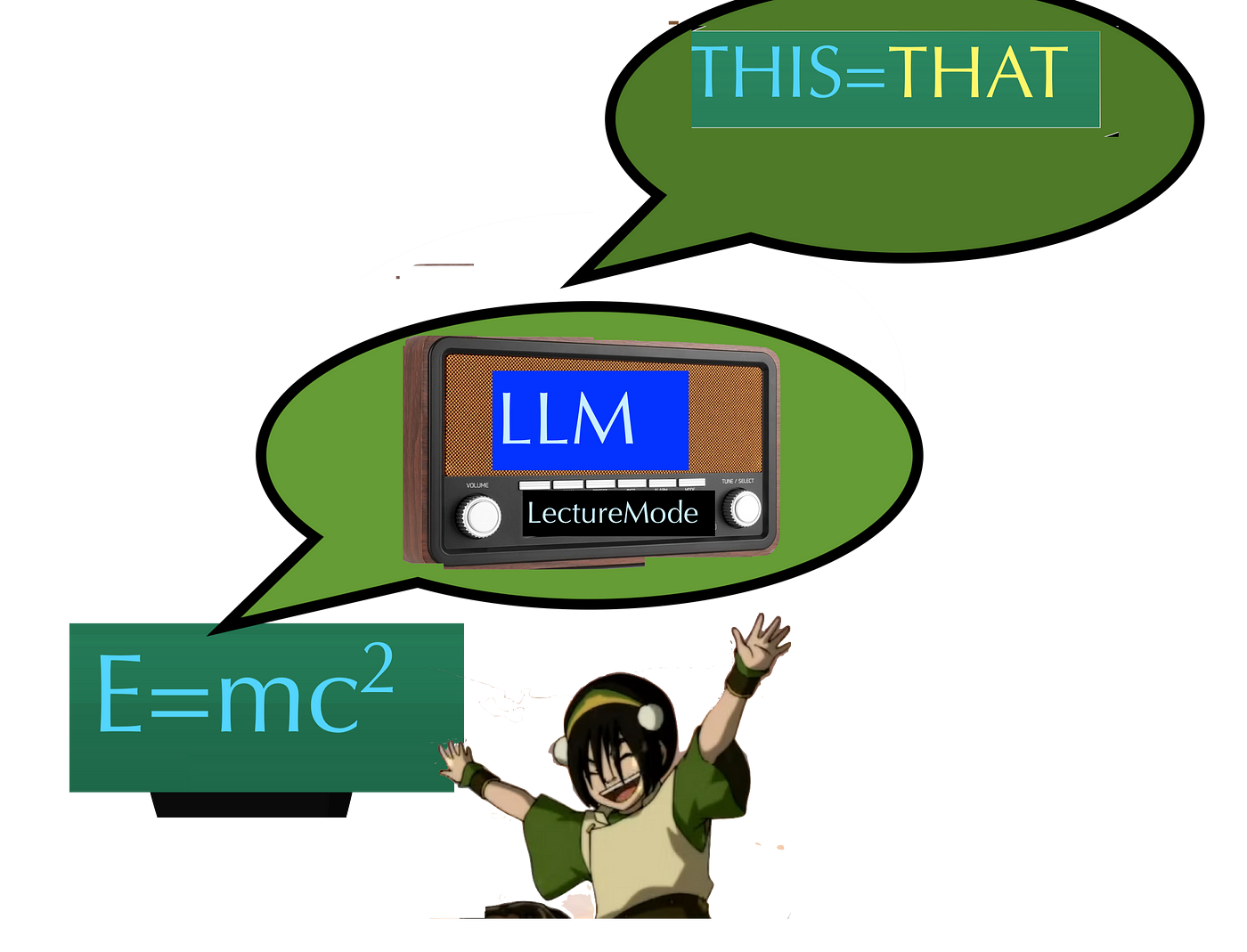

2. The mantra for solving the invisible problem is indeed, “Attention is all you need, “Which is, of course, the title of a well-known article that introduced transformers and the beginning of the LLM revolution. So, one can reasonably expect LLMs to provide a resolute solution. Here is how one can visualize such a device.

Of course, getting such an LLM setup for a most general formulation of solving for the invisible is a challenge, but I want to pose it here. Let me know if you do take it up.

P